IN ACTUALITY, THE PROBLEM OF STORYTELLING INVITES US TO CONFRONT OTHER NARRATIVE PATHS THAT BEGIN NEW WAYS OF MOVING THROUGH OUR SURROUNDS.

Uninhabitable places to feel where I was carrying my head

LUGARES INHABITABLES PARA SENTIR DONDE LLEVABA MI CABEZA

THE STORY OF MY MOTHER TONGUE

My mother’s name is Carmen Lydia Pérez. She was born in McAllen, Texas. She doesn’t accent her surname, as I did just now, and her maiden name, Guerrero, doesn’t appear on any government documents.

When my mother was a young woman, she weighed less than 100 pounds. She traveled with the rest of her family to Michigan to pick strawberries, seasonally.

The mother my mother came from was named Adelina Guerrero Fuentes. Her first name means «nobility» & comes from the Spanish, though I read somewhere online, while researching her name, that it originates from Ancient Germanic.

To this day, no one has been able to tell me where my grandmother was born. Her daughters trace her beginning to the state of Tamaulipas, along México’s increasingly walled-infrontier, but can say little more.

In Tamaulipas, my grandmother, who everyone called Nina, eventually married a man from Montemorelos, Nuevo León, which is a small city nearby Monterrey, in this same part of México that’s also known as the North. His name: José Guadalupe, with a diacritic on the «e».

I’ve always been drawn to the name Guadalupe. It’s religious (Our Lady of Guadalupe) & unisex while also Arabic (wadi: river/valley) & zoological (lupus: wolf).

The one story I know about my grandfather’s life in México is that he saw his brother crucified to a tree during the Mexican Revolution.

Sometime after this story, my two grandparents married. They had 5 children, first a stillborn, then Enriqueta, María Guadalupe, María Isabel, & Albino, before they fled to the United States, where they had five more: María Herlinda, Carmen Lydia, Juan Antonio, María Rosa, & Raúl. My mother says, & this has only been told piecemeal & within the past few years, that my grandfather lost a bet, or built up some other kind of insurmountable debt. There was also an altercation, a mysterious car accident, possibly murder, or at least death.

In the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, once my grandmother & her family had settled, she opened a 2nd-hand store & sold glass bottles of Coca-Cola out of an ice cooler. She tended a garden full of grapes & peaches she was very proud of in the front yard of her house, & in the back patio, her husband raised fighting roosters in a homemade coop.

Despite all her years in the United States, my grandmother never learned to speak English. She called me Cristóbal, not Christopher. Only years later, after she had died, did I realize it wasn’t my name she was saying but hers, holding onto my mother tongue.

THE STORY OF BORGES CHOKING

Today I’m watching La Poesía en Nuestro Tiempo on YouTube. Filmed on August, 26th, 1981, Jorge Luis Borges appears in conversation with Octavio Paz & Salvador Elizondo in the Capilla Guadalupana del Palacio de Minería in Mexico City. The three writers are discussing the enigma of time.

In the video, Borges is already blind. Octavio Paz, who’s moderating, fidgets in his chair. The third writer, Salvador Elizondo, smokes & drinks against a backdrop of the chapel’s mural of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

I look past the three writers to the golden cherubs surrounding the Virgin, behind them. A large part of the enigma of time asks that we be somewhere & translate what has been said elsewhere, at another time.

At least this is what I gather from Borges whose attempt at understanding our time can only come by way of example. Surprisingly, the writer known for infinite libraries & dreamt worlds within worlds thinks concretely.

«& the red winds are withering in the sky», I repeat after Borges who’s quoting Poe.

Borges is claiming that Poe was a mediocre poet who had the good fortune of being translated. One of his friends, he says, made the mistake of translating this line literally.

In the video, Borges, reciting his friend’s translation, gets stuck on the last word, maybe unwilling to inhabit someone else’s language, verbatim. It’s also possible he’s choking on a syllable that disagrees with him or that bad verse is injurious to the writer’s health. With one hand on his cane, the other shakes. Elizondo hunches over, too meek before the Argentine’s literary stature to know how to respond. He’s trying to make out what Borges is saying, but the sounds the octogenarian emits come from somewhere other than the tongue.

Later, I scroll down the video’s comments. Someone’s posted that Borges is speaking his alien language for the first time.

«Y los vientos rojos se desvanecen en el cielo», I say in my alien language, a Spanish that is familiar but has never felt quite natural or right.

You see, if Poe had the good fortune of being translated, someone tried finding the words to say what Poe was saying, elsewhere. Octavio Paz claims this is why Baudelaire saw himself in Poe. Poe wrote down what Baudelaire needed to translate into his own time.

THE STORY OF EL LIBRO VAQUERO

I don’t know when I started buying historietas mexicanas. An historieta’s a comic book in Spanish. I’ve always thought the word it comes from, historia, is ambiguous in everyday contexts. That’s because historia is cognate with history in English but can often be translated to story, a different word with a distinct meaning.

Stories incorporate fantasy, often taking part in fabrication & lies, all of which someone’s expressing subjectively in their telling, not unlike how it happens with history, really. But, in English, what the word history promises that the word story doesn’t is a speaking authority.

What’s nice about the Spanish word historia is that it seems untethered to maintaining these semantic & ideological differences, so much so that the irony is that another word for story in Spanish, cuento, continues to confuse what’s supposedly history & what’s merely story (puro cuento). Nonetheless, if you’re going to count (contar) anything you have to order it, & so even stories become habits of accounting. It’s somewhere here, jutting up against these ambiguities about fantasy & authority, about telling stories as part of history, & about translating for yourself whatever remains fabricated in the telling, that I read these Mexican comics.

In 2004, for example, the current president of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, then Head of Government of Mexico City, printed 2 million copies of Las Fuerzas Oscuras Contra Andrés Manuel López Obrador (The Dark Forces Against Andrés Manuel López Obrador).1 With a cover page featuring a black shark lying in wait before a crowd, he wrote himself into a story about the battle between the right & the left, turning it into a history of good & evil.2 This historieta followed the heels of Vicente Fox’s administration’s publication of El cambio en México ya nadie lo para (Change in Mexico Can No Longer Be Stopped).3 [p25-26]

But most historietas aren’t about politics, at least explicitly. When I was young, I used to secretly ogle them at the local supermarkets in my hometown in Texas, moving one eye slowly toward the small, square booklets while the other remained fixed on my mother’s shopping cart. At the time, the gun-toting men & curvy, helpless women, along with the titles in garish type that I silently read in Spanish, were forbidden. These stories, in a language on the cusp of being linguistically, but not culturally, foreign to me advertised the words «for men» («para hombres») on their cover pages.

Nowadays, my collection of historietas, poor but slowly growing, includes two issues of El Solitario, a prized copy of Las Chambeadoras, & a handful of El Libro Vaquero. The latter circulates more than 41 million copies per year.1 The best-selling historieta features various, nondescript white protagonists who adventure in the so-called Wild West.

How these blonde heroes translate the stories of a miner in Hidalgo or a bolero (shoe shiner) in Jalisco or a carpenter from Puebla, freshly emigrated to New Jersey, depends on a rare feat of the Western genre that, unlike speculative fiction’s para-worldly exophora, places itself at a frontier that makes up a history of conquering & policing all context. This history, in any case, recounts this all-too-familiar story to all of us who live on the frontier, even if for anyone living here, the extremity of «here» is only partially located by stories about conquering & policing. That’s because the wild condition of storytelling that comes hand-in-hand with living on the frontier foments an anti-domesticating & anti-cultivating orientation toward history. Whether this condition is artificial or natural matters little. I can say that it’s at times impossible to live here. Why? Because what’s told about the frontier erases what’s always been here, & the Western genre, in particular, is good at finding a way to view this place as if it were a tabula rasa for the American story.

In «Cazador de Indios», No. 1504 of El Libro Vaquero, the story begins with the Comanche Lucero de la Mañana (Morning Star), who escapes from Apaches who wish to rape her. Forced to enter a river & jump from a waterfall to save herself, she washes up unconscious along the riverbed at the bottom of the waterfall. A gold digger (un busca fortunas) then rescues her.

There’s nothing to say about this man, Donovan, except that his hair’s long & blond & that his jaw’s square.

Upon waking, Lucero de la Mañana falls in love with him for saving her and gives him her soul & body. What follows entails Lucero de la Mañana’s jilted lover, Puma Loco (Crazy Puma), dueling with Donovan to restore his honor. Puma Loco loses. The tribe chief Venado que Corre (Running Deer) then commands Donovan to capture Hacha Rota (Broken Axe), a traitor who has sided with the «Indian hunter» Herman Taylor. The hero must free himself of the Comanche tribe by completing Venado que Corre’s demands. Only then will they allow him to carry off Lucero de la Mañana into lontananza.

Number 1557 of El Libro Vaquero, «Búfalo Blanco», takes a slightly different approach. It centers the story of Ojo de Halcón (Hawkeye), a Shoshone «brave» who’s accompanied by his lover Torcaza (Eared Dove) & his white friend Kenny Ponder on a vision quest for the white buffalo that’ll turn the protagonist into a shaman, thereby restoring his destiny after he unwittingly killed the tribe’s current shaman, Mahpiya Ska (White Cloud, according to the historieta), when protecting the campgrounds from a Cheyenne raid.

The adventuring trio’s enemy is the gold digger Mitch Beadwell who’s teamed up with the sour, defeated Cheyenne after discovering that a coveted «fire necklace» makes up part of the booty.

Of course, the heroes defeat their enemies. Ojo de Halcón & his company then return from the mountains, blessed by the white buffalo. Siyotanka, a «wise woman» (wikahunka, says the historieta), bestows the new medicine man with the fire necklace. In a clever wink to El Libro Vaquero’s readership, the necklace turns out to be made of gold, Mexican coins. «Rojos no estar atados a metal amarillo», Ojo de Halcón says, giving the necklace to his white friend. The two part ways & the story ends.

By now I’m sure it’s obvious that I like to read El Libro Vaquero. The tropes it relies on tell me about the failure of inhabiting a place that’s resistant to classifying the laws of who’s what & how. Like a hawk soaring with a bird’s-eye view, or a caterpillar awaiting metamorphosis, I’m at the frontier, a place where stories entangle our histories until they even become foreign to us. Disentangling how El Libro Vaquero pits the Shoshone against the Cheyenne while it also portrays Donovan as a white savior dressed-up for a Mexican readership continually at odds with mestizaje might be one way to examine part-for-part how stories in the historieta get told. Still, the wild(er)ness of the frontier turns my attempt at telling this story into a desire for what lies beyond its made-up history.

I’m trying to find the words to say that it isn’t who we are at the frontier but how we live what becomes of it that causes us to reimagine our uninhabitable place in storytelling. Just look at how the various indigenous peoples portrayed in El Libro Vaquero all speak a Spanish that’s limited to the use of infinitives. Unbound by tense, the language giving shape to their experience refuses to agree with storytelling. Even if & maybe because El Libro Vaquero stereotypes agrammatical speech patterns to signal so called primitive alterity, it inadmittedly creates a chink in its story. An ulterior one now becomes possible to tell outside of history.

When Lucero de la Mañana, naked & enraptured in Donovan’s arms, exclaims, «¡Ooh, Pálido! ¡Al fin, tenerte! ¡Y-Yo morir de gusto!», are her uninflected verb choices of «to have» & «to die» equally unlimited & indefinite in their embrace? Are they conspicuously infinite? Is her expression of pleasure unbound to the time of its enunciation, as well? & is she neither regimented by history nor indicating to her white lover her subservience to his settler temporality?

Might she be translating for everyone outside of the colony’s history? Or could it be that she is seeking not a primitive but a prehistoric & preternatural speech-act that un-domesticates her being? What if, then, the wild condition of storytelling ambiguates language’s inflection of time & turns it into an account of how history is unable to tell the story of bodies at frontiers?

This is a tall order for El Libro Vaquero or any other historieta, for that matter. El Libro Vaquero’s «Búfalo Blanco», reserves the last 30 pages of its issue for a mini-historieta from the Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público (Office for the Treasury & Public Credit). Even so, each issue forms part of the story of a lone reader like me who’s now in the thick of it with everyone else.

THE STORY OF MOSQUES IN MEXICO

When Hernán Cortés came to conquer México, he wrote back home, saying he saw mosques. This account is relayed in Primera Carta de Relación to Emperor Charles V.

This is one of the wildest stories I know, & it is one that I always tell.

THE STORY OF PEYOTE’S TAXONOMY

Seventy-two years after Primera Carta de Relación, Juan de Cárdenas, a Spanish scientist, wrote in Problemas y Secretos Maravillosos de las Indias:

Quéntase con verdad del peyote, de peyomate y del hololisque, que si se toma por la boca sacan tan deveras de juyzio al miserable que los toma, que entre otros terribles y espantosos phantasmas, se les presenta el demonio y aún les da noticias (según dizen) de cosas porvenir…4 [p51]

I first read this quote from a soaking wet page, in Mexico City’s rain. I was stuck under a cybercafe awning in the neighborhood Narvarte. Juan de Cárdenas’ 1591 indictment of peyote made up one of the three epigraphs for José Vicente Anaya’s book, Híkuri, which I had bought that day from one of the book’s editors, having traveled to her home to pick up the small & hard-to-find edition before I caught a flight back to Palestine the next day. It was 2016, & the 2014 reprint of the book, first published in 1978, formed part of Malpaís Ediciones’ Archivo Negro de la Poesía Mexicana, a collection containing reprinted works like Kin Taniya’s Radio: poema inalámbrico en trece mensajes.

At the time, I was searching for a type of poetry beyond the Infrarealist depiction of walking backwards into the horizon. I imagined Híkuri would offer a clue. The book-length poem’s about ingesting peyote. After reading it, I learned that it positions a poet who’s condemned to tell the story of what’s already been told.

Anaya’s like the West African griot. Or, more appropriately, he’s like one of México’s escribanos, a dying profession of community writers who beyond notarizing documents in town squares also write love poems for the illiterate. This kind of poet of scribbled napkins & faithful public service holds onto enough of history to strive to translate everything outside it into a story that has yet to find the right words for its own telling. He & the writing encounter the problem of storytelling.

On top of that, Peyote’s tendency to turn any experience into an entangled account of frontiers trespassed & transgressed leaves Anaya with no other life but one of a pariah, & I think it’s one of the most difficult positions anyone could share their story from. In the final pages of his poem, the poet gives up on the world of writing, stating, «El Verdadero Nombre no se escribe», as if saying what can’t be recorded & accounted for complicates how we fantasize about truth—«Quéntase con verdad», de Cárdenas demands, right?4 [p117]

Truly, the problem of storytelling invites us to confront other narrative paths that mark new ways of moving through our surrounds. For the poet, the fact of enunciation seems to be enough, at least when wayward. He says (writes):

He dicho mis visiones———y sigo el

trayecto que no acaba en

cada momento noche

y día———la maravilla de ocupar

un espacio que todo lo cambia4 [p90]

Is it a truism or poetry to say that everything changes space? That «here» is enough of a trajectory to give dimension to everywhere? That visions of lands & peoples inhabiting a river delta, mountains, canyons, arid deserts, & vast brushland along a 1,953 mile border that was once much more amorphous, much more contested, & which included spaces such as Nueva Vizcaya, Nuevas Filipinas, Nuevo Santander, Nueva Navarra, & Baja & Alta California, the last two named after a fictional island ruled by a black queen, along with the places that were also here— the very real Apachería, the myth of Aztlán, the mirage of El Dorado, & so on—provoked a concept of the west that was wild in its telling? That was equally about the unknown of being as well as being unknown, like I have been, here?*

* The following lines from Ahora me rindo y eso es todo by Álvaro Enrigue5 inspire this long, unruly sentence about seeing & naming what’s here: «No sé bien qué implica esa urgencia de las naciones modernas por definirse como pobres de pigmento frente a otra –otras– que les parecen más antiguas, menos recién llegadas: para los historiadores mexicanos, todos eran blancos menos los indios, que eran los que llevaban más tiempo en la zona; para los historiadores estadounidenses, los mexicanos, que llevaban ahí más que ellos, son también no-blancos, como los apaches. Y luego están los negros, a los que ni siquiera mencionan, y los chinos y filipinos que migraron a lo que hoy es el suroeste de Estados Unidos durante el siglo XIX. Dividir ese mundo que germinaba en indios y blancos o en indios, blancos y mexicanos –tres categorías incomparables entre sí dado que una es la nominación inexacta de la población de todo un continente, la otra un color y la tercera un gentilicio– es, por decirlo con cautela y elegancia, una pendejada. (...)

» La guerra por la Apachería nunca fue entre blancos e indios: fue entre dos repúblicas mixtas y una nación arcaica que compartía una sola tradición y una sola lengua. Los indios no llamaban blancos a los mexicanos. Los llamaban nakaiye: ‘que van y vienen.’ A los gringos los llamaban indaá, ‘ojos blancos,’ nunca ‘pieles blancas.’

» Los apaches nunca pensaron que pelearan contra unos blancos, son los historiadores blancos –mexicanos y gringos– los que piensan que los apaches pelearon contra ellos».

«En esta propulsión de nervios / ¿Qué ves, / en el lugar que pisa tu cabeza?», Anaya writes.4 [p52] These lines were already Antonin Artaud’s when he said, «To take a step was for me no longer to take a step; but to feel where I was carrying my head».6 [p45] Before Anaya, Artaud worked through his own entanglement of the time of storytelling, writing in The Peyote Dance about the body «quartered in space».6 [p9] Written while imprisoned in French asylums, the book records Artaud’s experiences with the Rarámuri in 1936, when he traveled to Chihuahua, México to see who he was calling an antediluvian, «primeval» people among whom he wouldn’t be a tourist but an accomplice to the story.

The Peyote Dance is way more plagued & problematic than Híkuri. It’s also more interesting. The book’s mainly about Artaud, though it’s also about peyote. Unsurprisingly, it turns out to be wrong about a lot of things. Artaud calls the Rarámuri Tarahumara, for one, & not their endonym, which itself refers only to male tribe members. A worse error in the initial pages reveals Artaud’s belief that the Rarámuri descend from the Maya. The book’s chapters, «The Race of Lost Men», «The Land of the Magi Kings», & «The Rights of the Kings of Atlantis», also feel quixotic and picaresque.

In effect, The Peyote Dance hashes out a story Artaud uses to classify what he knows deep down he’s only translating, & yet, somehow, an orientalist spirit fails to grab hold of the book. It’s just so that in a postscript appearing in the middle of it, Artaud revises the way he transcribed Christianity onto every aspect of his story. He blames his mania on his forced religious conversion while in solitary confinement in Rodez. He wrote the chapter «The Peyote Rite», he claims, while undergoing electroshock therapy & poisoned by «at least one hundred & fifty to two hundred recent hosts in [his] body».6 [p43] This same Artaud decided that the first work for the Theater of Cruelty would be about the conquest of México. Its spectacle would broach «the alarmingly immediate question of colonization & the right one continent thinks it has to enslave another», whereby it would question, from the perspective that «everything that acts is cruel», «the real superiority of certain races over others» & show «the inmost filiation that binds the genius of race to particular forms of civilization».7 [p126-127]

I mean, in many ways, the transfiguration Artaud wished for among the Rarámuri in México desired to be as equally cruel & salvific as the transfiguration of Christ. It would take crucifixion or something close enough to get t/here because the surrealist wanted to disaffiliate from Europe or at least exorcise himself of its worst demons that, like Juan de Cárdenas’ description of peyote, spoke of things to come. It didn’t matter if this future foretold rising fascism in Europe, anti-indigeneity in México, or the drab reality of Marxist art. When Artaud wrote, he wrote to find a place for himself in myth, rather than history. But as a storyteller, Artaud could only order the knowledge that comes with appropriating from the experience of inhabiting the other side of the frontier. This type of people(ethno)-writing(graphy) believes in the task of decolonization but finds it impossible to disengage from its own fabricated history aligned with theft.*

* My own thoughts on Artaud are both confirmed & challenged in various places of Alejandra Pizarnik’s more succinct & coherent study of the poet, translated here by Cole Heinowitz8: «The main works of the ‘black period’ are: A Journey to the Land of the Tarahumaras; Van Gogh: The Man Suicided by Society; Letters from Rodez; Artaud the Mômo; Indian Culture; Here Lies & To Have Done with the Judgment of God.

» They are indefinable works. But to explain why something is indefinable may be a way –perhaps the noblest way– of defining it. This is what Arthur Adamov does in an excellent article in which he lays out the impossibilities –which I sum up here– of defining Artaud’s work:

· Artaud’s poetry has almost nothing in common with poetry that has been classified & defined.

· The life & death of Artaud are inseparable from his work ‘to a degree that is unique in the history of literature.’

· The poems of his last period are a ‘kind of phonetic miracle that ceaselessly renews itself.’

· One cannot study Artaud’s thought as if it had to do with thinking since Artaud did not forge himself by thinking.

» Many poets rebelled against reason in order to replace it with a poetic discourse that belongs exclusively to Poetry. But Artaud is far from them. His language has nothing poetic about it even though a more effective language doesn’t exist.

» Given that his work rejects both aesthetic and dialectical judgements, the only key that can provide a reference point is the effect it produces. But this is almost impossible to speak of since the effect is the equivalent of a physical blow. (...) Reading the late Artaud in translation is like looking at reproductions of Van Gogh’s paintings. And this, among many other causes, is due to the corporeality of the language, to the respiratory stamp of the poet, to his absolute lack of ambiguity.»

Maybe this is why the surrealists loved stealing whatever they could, whenever. This form of transfiguration that culture promised transgressed one frontier after another until the violence it had caused ended up creating supposedly new subjects that, in actuality, the surrealists were only «discovering», «unearthing», «reviving» from places that seemed like a new world. Bataille, for instance, could not be more brutally honest when writing about indigenous America when he said that the Aztecs were «poles apart» from Europe, morally. Because of unthinkable acts such as human sacrifice, Aztec civilization seemed «wretched» to Europeans, Bataille claimed. Artaud, on the other hand, proved how envious the entire enterprise of people writing could be, remarking, «Peyote, as I knew, was not made for Whites».6 [p48]

Prior to traveling to Chihuahua, Artaud published in La Nacional the essay, «What I Came to Do in México». «Bajo pena de muerte, México no puede renunciar a las conquistas actuales de la ciencia, pero tiene en reserva una antigua ciencia infinitamente superior a los laboratorios y los sabios», he writes.9 Translated, he was saying, «Under pain of death, México can’t renounce current scientific conquest, but it keeps in reserve an ancient science infinitely superior to laboratories & scientists». In this same essay, Artaud also claims that beneath Western science are other «hidden», «unknown» & «subtle» forces at work that are not yet under the domain of science—but that could be.

I recently found out that before coming to México Artaud had read Alfonso Reyes’ poem, «Yerbas del Tarahumara», published in 1929 & extant in French translation. The poem’s final stanza ends with the quatrain, «Con la paciencia muda de la hormiga,/ los indios van juntando sobre el suelo/ la yerbecita en haces/ —perfectos en su ciencia natural».10 («With an ant’s mute patience/ the indians go about bundling/ little herbs on the ground/ perfect in their natural science») It presents a story about what Artaud calls in The Peyote Dance «the whole geographic expanse of a race».6 [p12] It’s a poem that begins the fieldwork that would classify Artaud’s schizo-poetic mythos & which would later define Anaya’s reclamation of indigenous alterity & its subject-altering plant, rooted to the nativity of place. All the while, the poem looks from a distance, outside-in, to find a way to translate where that place is.

That science recounts indigenous knowledge in the service of the poem only adds to storytelling’s complicity in all kinds of narrative theft, both historical and ongoing. The poem goes like this: Reyes writes that the Rarámuri have again descended from the mountains after another bad year. He speaks of their unsettling beauty while narrating their forced Christian conversion. Indigenous syncretism, he suggests with either too little or too much imagination, permits the Rarámuri to eat peyote & enter a «metaphysical drunkenness» that compensates for the existential burden of walking the earth.

«Yerbas del Tarahumara’s» key stanza turns the poet into a botanist who lists different native herbs like horseweed (simonillo; Conyaza canadensis), Mexican marigold (yerbaniz; Tagetes lucida), & oshá (chuchupaste; Ligusticum porteri), which the Rarámuri sell in town squares. In the poem, Reyes prefigures Artaud’s deep sense of loss that comes from how non-indigeneity fucks up the story of place when in the same stanza he speaks of the «urbane envy» (Samuel Beckett’s translation) of the city’s whites who purchase the Rarámuris’ secret herbs.

Reading «Yerbas del Tarahumara», I’m like a wide-eyed & confused Artaud. Unknown forces compel me to say that while botany was establishing a taxonomy to identify, classify, & describe plants, like peyote, these plants already maintained an ulterior & ancient—or maybe just simply different—life.

Peyote’s scientific name, for what it’s worth, is Lophophora williamsii. The species fits into a taxonomy of which its genus is lophophora; its subfamily: cactoideae; family: cactaceae; order: caryophyllales; its clades: all of eudicots, angiosperms & tracheophytes; & its kingdom: plantae.

The name Lophophora williamsii, itself completely foreign to the cactus’ region, is attributed to the French botanist Charles Lemaire & the American John Coulter. In 1894, Coulter would publish Preliminary Revision of the North American Species of Cactus, Anhalonium, & Lophophora under the auspices of the United States’ Department of Agriculture who had asked him to «secure a large amount of additional material in the way of specimens & field notes».11 [p91] Making his way to the U.S.-México frontier in Texas, where I call home, Coulter wrote a compendium whose final pages revised the limited Western botanical knowledge that existed on peyote. He offers these words:

Hemispherical, from a very thick root, often densely proliferous, transversely lined below by the remains of withered tubercles: ribs usually 8 (in young specimens often 6), very broad, gradually merging above into the distinct nascent tubercles which are crowned with somewhat delicate pencillate tufts, which become rather inconspicuous pulvilli on the ribs: flowers small, whitish to rose: stigmas 4.

Along the Lower Rio Grande, Texas, & extending southward into San Luis Potosi & southern Mexico.11 [p131]

Encountering this description, I think about Artaud & his revelation that peyote was not made for whites. I turn to The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacological & Its Applications, which lists over 50 «folk names» for the cactus, many of them originating from various indigenous tribes across America. Apart from Lophophora williamsii, the cactus is called wokowi (Comanche), pee-yot (Kickapoo), azee (Navajo), chiee (Cora), hunka (Winnebago), & camaba (Tepehuano), among other names.12 [p1023] The name «peyote», some might not know, derives from the Nahuatl word, «peyotl». But the Rarámuri, who make up the subject matter & develop the imaginaries of the three poets I have been reading, prefer the word «híkuri».

Elsewhere, a different book I have says that the Rarámuri of Rejogochi believe that híkuri make up a special class of beings that take on human form. These beings either help or hurt the Ráramuri, interacting with them based on a relationship of reciprocity that, if its balance is disturbed, provokes híkuri to retaliate by capturing human souls.13 [p131]

In the Rarámuri of Rejogochi’s taxonomy of the universe, one that’s markedly different from botany’s explanations of belonging, peyote forms part of a group of plant people that accompany humans on Earth.13 [p75] Because peyote has agency, it has a soul too, the thinking goes. Or rather, peyote’s soul, which bears life, creates an agent the Rarámuri interact with, cautiously, & in varying degrees of reverence & fear.

In their language, the words for «soul(s)» are ariwá & iwigá, both also meaning «breath».13 [p155] When the Rarámuri breathe, a portion of their souls enters & exits their bodies that act like homes.

In 2007, José Vicente Anaya read Híkuri to a group of Rarámuris living in makeshift homes on the outskirts of Ciudad Juárez, along the Chihuahuan-Texan frontier.14 [p122-123] However strange the experience, the group loved the poem & «the respiratory stamp of the poet».8 For one, it transported them back to the Sierra Tarahumara & transfigured the time of storytelling by disaffiliating it from history. It also gave them a place to breathe.

It would make sense, then, why the Rarámuri don’t traditionally write & instead tell stories. It isn’t a way to resuscitate what’s dead, but one to remain light-footed on Earth, as their own name indicates.

THE STORY OF THE SEARCH FOR ALONZO & ABELINA

It was early afternoon January 23rd, 1890, when Eulalio Salinas, Municipal Judge of Los Aldamas, Nuevo León, Mexico saw a local citizen approaching City Hall. Juan Gonzalez Peña had a week-old infant in his arms. Gonzalez-Peña, a local police officer, had come to register his first daughter’s birth. Paula was born in his home in Los Aldamas at 8:00pm on January 23rd, 1890. Although his own parents were dead, his wife’s mother, Antonia Rangel, was alive to see Paula’s birth.

Almost two years later, María del Rosario gave birth anew to a second daughter. Juan took his new daughter to City Hall eleven days later, on the morning of November 21st, 1891, to register her birth. The new Judge, Luciano Peña, noted all the important details:

Name: Abelina González Peña

Date of Birth: November 10th, 1891

Place of Birth: House of deceased

Francisco Alaniz

With him to witness the act were Alfredo Elizondo & Juan P. Garza.

Less than a year later, the life in María del Rosario’s body was gone. It was said that she had died of «susto». Evidently she had been swimming across Río Los Aldamas in the face of an impending flood with three-month old Abelina in her arms when she spotted a rising wave approaching her. Frightened, she quickened her pace & managed to cross the entire river without mishap. However, she probably went into a state of shock, for she died shortly afterwards in 1892.

Juan, her husband, must have grieved deeply after his young wife. He had become a young widower with two young children, an infant & a toddler. So many thoughts must have crossed his mind… How was he going to raise two young children by himself? How was he going to provide a mother image for his daughters? His own mother had already passed away. He could not bring himself to marry another woman, although he realized that his children needed a mother.

Ursula Alaniz González, Juan’s first cousin, must have sympathized with his apparent anguish. Although a good-looking woman, she had never married. The customs of her day dictated a woman marry in her teens. When Juan became a widow, she was 27 years old & faced a great likelihood of spending her old age alone.

She decided to help her first cousin raise his children. The girls had known their natural mother for such a short time, they came to see Ursula as a mother & called her «Mama Lolita».

Although the details surrounding Paulita Gonzalez Peña’s move are yet unclear, it is known that she was raised by the family of the man she eventually married: Victor Carrillo. The Carrillos were a family that was financially comfortable, even rich by the standards of the townspeople. They resided in the same town of Los Aldamas.

In the meantime, «Mama Lolita» raised Abelina from infancy to womanhood in the house of her father, Francisco Alaniz. Juan resided with her, as did her brothers, Anastacio, Félix & Pablo. She had two other sisters, Felicita & Nazaria, both of who eventually married. Pablo also married. «Tacho» (Anastacio) & Félix remained bachelors all of their lives.

ACTA NÚMERO (14) CATORCE MATRIMONIO DE: ALONSO PÉREZ Y ABELINA GONZÁLEZ

En la Villa de Los Aldamas a los 21 días del mes de agosto de 1909 Mil Novecientos nueve a las nueve de la noche ante mi Luciano Peña Juez de Estado Civil de esta Municipalidad, hallándome constituido en la casa de la Sra. Ursula Alanis presentes el Señor Alonso Pérez y la Srita. Abelina González ambos célibes el primero de 22 años de edad hijo legítimo de los Finados Ramón Pérez y Teresa Solis, vecinos que fueron de Los Herreras, y la segunda de 18 años de edad, hija legítima de Don Juan González y Doña Rosario Peña (Finada) vecinos de esta propia Villa, de profesión el pretenso labrador. Ambos contrayentes dijeron: Que habiéndose presentado con objeto de contraer matrimonio el día 2 del mes en curso, a cuyo acto ocurrió también el padre de la pretensa dando su consentimiento, así como lo hace ahora para que su hija contraiga el matrimonio consertado por ser menor de edad, y por otra parte habiendo sido hechas las publicaciones en la forma legal sin que se halla presentado impedimento alguno según aparece de las constancias respectivas, piden al Señor Juez autorice su consertada unión. Interrogados los contrayentes en los términos que la ley ordena hicieron su formal declaración de ser su voluntad unirse en Matrimonio y entregarse mutuamente como Marido y Mujer: en esta virtud yo Luciano Peña Juez del Estado Civil de esta Villa hice la siguiente declaración: En nombre de la Ley y de la Sociedad, declaro unidos en perfecto, legítimo e indisoluble matrimonio al Señor Alonso Pérez y a la Señorita Abelina González. Fueron testigos de este actos los Señores Albino Peña, Luís Elizondo, casados, labradores y de esta vecindad, leída esta acta a los interesados y testigos la ratificaron y da conformidad. Fueron conmigo el juez. Doy fe. Luciano Peña.

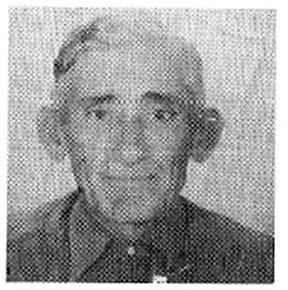

Abelina grew up to be a strong-willed, determined person. She was said to be a master of conversation & a talented businesswoman. Very early in life, she learned the skills of a seamstress, most likely from Ursula (Mama Lolita). At field labor, she was the best—she would let no one get the best of her. An extremely competitive woman, she attempted to master all that caught her interest.

The man that caught her interest & her heart was Alonzo Pérez Solis. Alonzo, a horse tamer by profession, was from the nearby ranch of La Laja. Born of Ramón Pérez López & Teresa Solis in 1888, he came from a family of nine—four brothers & four sisters by his father’s second marriage & five more by his father’s first marriage to Rita Alaniz. By all accounts, he came from a very large family in comparison to Abelina’s family!

The details of their courtship are few. It is known that they officially registered their intentions to marry on August 2, 1909, & that Juan González gave his consentment on public record, as at 18 years of age she was still considered a minor. Alonzo was 22 years old at the time. They married in La Villa de Los Aldamas in a civil ceremony on August 21, 1909 in the home of Ursula Alaniz. The same Judge that registered Abelina’s birth married them: Luciano Peña. Juan González was the only parent alive to see the marriage. Alonzo’s parents had already passed away.

Abelina & Alonzo began their married life in the same house that Abelina grew up in Ursula’s home. They lived there together with Juan González Peña & Ursula Alaniz González, both of whom lived to see the children born to them between these years, only three survived to adulthood: Miguel, the eldest son, born July 5, 1911; Juanita, born January 10, 1914; & Ramón, born August 23, 1916. The other two were also named Juana & Ramón. Juana was born October 23, 1912 & died February 17, 1913 of «fiebre intermitente» (intermittent fever). Ramón died at five months of age on October 31, 1915 of diarrhea.

It is known that Abelina gave birth to at least five other children that died in infancy; among them a set of twins.

Their life in La Villa De Los Aldamas revolved around a «tienda de abarrotes», a grocery store business that Abelina & Alonzo managed. She also continued to sew clothing on the side. Alonzo brought in a good amount of money as a horse tamer. Juanita, his daughter, still recalls that her father always wore a red handkerchief around his neck, & used it to blindfold the wild horses he was given to tame. Abelina, at times, accompanied him on horseback on the job! The sight of the two on a wild bronco must have been a breathtaking site.

The family traveled to a ranch that Juan González gave to his son-in-law, Alonzo. They raised livestock, goats, poultry & other animals. Alonzo milked the cows & sold the milk at the train depot in Los Aldamas. The ranch, according to Juanita, was very large. It was fenced & had a house on it. She said twenty-five «almudes le cabía». By the standards of the townspeople, the family was a prosperous one.

Abelina & Alonzo had married in 1909, a year before the Mexican Revolutionary War was declared. As the war wore on, the political climate in the country worsened. Men were drafted from all over Mexico into both political factions.

By the time Ramón was born in 1916, the family had made a decision to leave the country. It was difficult to leave everything behind—the grocery store, the ranch, the livestock, & most of all, Mama Lolita & Papa Juan, who had done so much for them. Their lives, their children’s lives, & their future as a family were at stake, however, & the move to the United States represented their only hope. As all the priests in México were in hiding due to the Revolution, Ramón could not be baptized in México. He was baptized in Roma, Texas on August 9, 1917 in the local Roman Catholic Church.

Late 1917 or early 1918, Alonzo & Abelina packed what they could into their «waguin», took their three children; Miguel, Juanita, & Ramón, & said good-bye to their family, friends, & to la Villa De Los Aldamas. They traveled north & entered the United States through the Laredo port of entry. They headed further north towards Hearne, Texas, where Susano Pérez Solis lived on his ranch. Susano, Alonzo’s brother, lived on the ranch together with Preciliano, another brother. The three brothers lived together on their ranch for a short period of time. It was not the first time they had worked together. In 1907 or 1908, Alonzo, together with several brothers (Preciliano, Susano, Ramón, Tirso, & one half-sister, Dorotea) had migrated north to Hearne, Texas to work. Alonzo had returned to get married in 1909.

Alonzo worked in «la hacha», that is, clearing land with an ax in order to use it for agricultural purposes. After a short period of time, Alonzo decided to move his family to San Antonio to work in the fields picking «chicharo». According to Miguel, Alonzo’s son, he then purchased another «waguin» with a pair of burros (instead of mules, as burros were less expensive to feed). They went to Moore, Texas for more fieldwork. Eventually they moved to Alamo, Texas in the Rio Grande Valley, where they rented a small frame house & continued their northern migrations for agricultural work. María Del Rosario was born in San Juan, Texas on March 29, 1918. On one of the trips to Moore, Texas, Abelina gave birth to María Ana, on March 19, 1922. A doctor was brought in from Pearsall to attend the birth as there were no doctors in Moore. Thus, María Ana’s birth was registered in Pearsall.

Abelina purchased a small house in Alamo on Birch Street. Alonzo & Abelina’s last child was born on April 10, 1925 in Alamo, Texas. They named him Jesus María. Doña Anselma Sloss assisted in the birth.

Alonzo Pérez Solis became ill at some point in time. His trembling hands, slumped body & uncontrollable salivary glands led him to seek medical help all over, but to no avail. Although he grew so ill he was unable to work, Juanita recalls, he would find a way to cook hot meals for the family & bring the food to the fields to them. He sought medical attention as far as Laredo, Texas & finally, in a last attempt, he went to Los Espinasos, Nuevo León, México, to see El Niño Fidencio, a curandero who promised to heal all the ill on a March 19, a Saint Joseph’s Day, in 1926 or 1927. Susano & Preciliano gave him the money he needed for the trip & he left the Rio Grande Valley for the last time. Brígida Solis, a distant cousin, accompanied him on the train because she wanted El Niño Fidencio to heal her son as well. In an interview with María Del Rosario Pérez González in 1977, Brígida told her that the three had arrived in Los Espinasos only to find that the sick were required to crawl up a hill of stickers without shoes. She despaired & begged Alonzo to return to her, that they would not be cured there. However, Alonzo reportedly answered that he would stay & added «salúdame a todos allá». Brígida returned with her son on the train. Alonzo stayed.

He never returned.

His children & wife assumed he had died. Years later, Miguel went to Monterrey, a short distance from Los Espinasos, to look for his father at the home of some cousins he hoped might have seen him. The cousins told him that Alonzo had been there before going to Los Espinasos, but had not returned.

In the meantime, back in Alamo, the family continued their northern migrations to work. Saturnino Alemán, a friend of the family, traveled with them & helped them as they struggled financially & emotionally to recuperate from the loss of their father.

The winter of 1928 saw the family in Georgetown, Texas working the fields as usual. Abelina began to feel ill. Her constant coughing became uncontrollable & produced blood. The children worried about her. Sixteen-year-old Miguel stayed with the children while Saturnino & Juanita took her to a hospital in August where she was hospitalized for eight days. Although the blood was stopped the doctors offered a dismal prognosis: she would die in a short time. The children should take her home, they said, where she could be made as comfortable as possible. They added that although the blood production was under control at the time, it would begin again and that there was nothing more that could be done. The diagnosis: double pneumonia.

Juanita, María Ana, Jesús, & Saturnino took Abelina home to Alamo in December, 1928, while the rest continued to work in Georgetown. Abelina sought medical treatment with a U.S. Government doctor in Donna, Texas. He prescribed cough syrups & pills that Juanita administered to her mother faithfully. Abelina’s condition worsened. She grew thinner & thinner.

The seasons come & go, bringing life & taking it as well. The winter of 1928 left in March or April of 1929, taking with it Abelina González Peña de Pérez.

Juanita, Abelina’s daughter, recalls the day in which her mother died. She was planting orange tree seeds in the front yard when she heard her mother calling her. «Ven hija. Dame la medicina». Juanita was puzzled. She knew it was not yet time to administer the medication. She went inside to reply, «No, Mamá. Todavía no llega la hora».

Abelina must have known that the spirit of life was rapidly leaving her body. Undoubtedly, she wanted the warmth of her child in her last moments. «Ven hija», she said, «quiero que me agarres en tus brazos».

Juanita obediently took her mother in her arms. The fourteen-year-old gazed wonderingly at her mother’s long, thin body. As she held her closely, she noticed the warmth in Abelina’s body fading slowly. Alarmed, Juanita shook her mother’s face. «Mamá! Mamá!» There was no response.

The moment she had been dreading had arrived. Anguished, Juanita began to scream. The neighbors came running & Juanita fainted, in shock. She awakened, she recalls, about four hours later. Her mother had been laid on the bed in the customary position of the dead. Neighbors had lavished flowers at her bedside. She laid in state 24 hours, while Saturnino arranged her interment. He purchased a lot in the Pharr Cemetery, a coffin & a wooden cross. Before her burial, he photographed her. He was saddened that Miguel, Ramón, & María Del Rosario could not be present at their mother’s funeral & wanted to give them a final keepsake of their mother. Unfortunately, the roll of pictures was defective & the pictures were not developed.

Juanita, María Ana, & Jesus stayed with Paulita González Peña, Abelina’s sister, after the funeral, while Ramón Peña worked to locate the rest of the children in Abeline. As soon as Miguel received word that his mother had died, he returned with Ramón & María del Rosario, to gather the other three children. They rented a house in San Juan, close to Tía Lencha de la Garza, Roque Garza’s mother.

The house on Birch Street in Alamo had held too many painful memories for the moment.

A flood, common in those days, took away the wooden cross marking the final resting place of Abelina González Peña de Pérez. To this day, her children do not know where to lay a bouquet of flowers in her memory.

Paulita González Peña married Víctor Carrillo in Los Aldamas, Nuevo León, México & had five children:

· Claudio

· Carolina

· Cleotilde

· Arnulfo

· Enriqueta

After she became a widow, she married Refugio Galván in San Juan, Texas. She had five more children, two of whom died:

· Guadalupe

· Consuelo

· Gudelia

· Lupita

· Arturo

Paulita died September 8, 1963 in McAllen, Texas of pulmonary emphysema.

Juanita married Ricardo Hernández on January 14, 1933. She gave birth to 12 children, one of whom died in infancy. Their names & dates of birth are:

· María Luísa: October 26, 1933

· Pablo: December 8, 1935

· Abelina Josephina: October 16, 1936 – December 15, 1975

· Juan José: November 5, 1939

· Ricardo: August 22, 1941

· Elvira Herminia: [DIED IN INFANCY]

· Elvira: February 26, 1944

· Elizabeth: October 1, 1946

· Mirthala: March, 1948

· Miguel Alonzo & José Manuel: July 16, 1952

· Bertha Alicia: December 31, 1953

She currently lives in San Marcos, Texas with her son, Ricardo.

Miguel then married Ofelia Ballí on August 20, 1935. They had one child, a daughter;

· Alicia: April 14, 1954

Miguel hauled hay & sold posts for a living & continues to do so to this day.

María Ana married Pedro Natal in Beeville, Texas on June 21, 1940. They raised their 10 children outside San Marcos, Texas in a house they had built in the country;

· Ana María: December 8, 1940

· Pedro, Jr.: August 20, 1942

· Abelina: April 18, 1944

· Guadalupe: April 1, 1946

· Juan Alonzo: December 21, 1947

· Miguel: October 29, 1949

· Yolanda: May 21, 1951

· Jesús: May 11, 1953

· Acensión Carlos: January 21, 1956

· Ramón: September 13, 1959

Paulita's 2nd husband

Age: 31 years. Abelina's older sister

María Ana returned to school to further her education & became a nutritionist. She works at Hillside Manor in San Marcos, Texas.

María del Rosario followed, marrying Aurelio Barrera Ramos in Alamo, Texas on September 22, 1940. The two continued to live in Abelina’s house on Birch Street with Ramón & Jesús until they had saved enough money working at the «Teatro & Tienda El Nuevo Mundo» to build the house they raised their 9 children in on Acacia Street in Alamo. Two other children died in infancy;

· Gertrudis: January 5, 1943 [DIED IN INFANCY]

· Gertrudis: June 27, 1944

· Abelina: August 9, 1946

· Clarita: October 1, 1947

· Aurelio, Jr.: December 18, 1949

· Dolores: February 12, 1950

· Margot Yolanda: August 15, 1953

· Pedro Alonzo: May 7, 1955 – May 10, 1955

· María Ana: September 30, 1957

· Pedro Alonzo: April 23, 1959

· Miguel: August 30, 1961

Ramón & Jesús María were drafted into the Second World War. They wrote regularly to María del Rosario, Juanita & María Ana.

Ramón courted Francis Torres for many years before he could save enough money for the wedding. They married on September 1, 1946. They had six children, the first of whom died in infancy.

Ramón & Francis’ children:

· Mike Raymond: November 21, 1951

· Eddie Rene: April 16, 1954

· Lee Roy: October 31, 1955

· Reynaldo Alonzo: Dec. 31, 1959 – Sept. 5, 1985

· Belinda Rachel: August 7, 1962

Ramón raised his children on his ranch outside Alamo. He also hauled hay with his sons throughout his life & does so to this day.

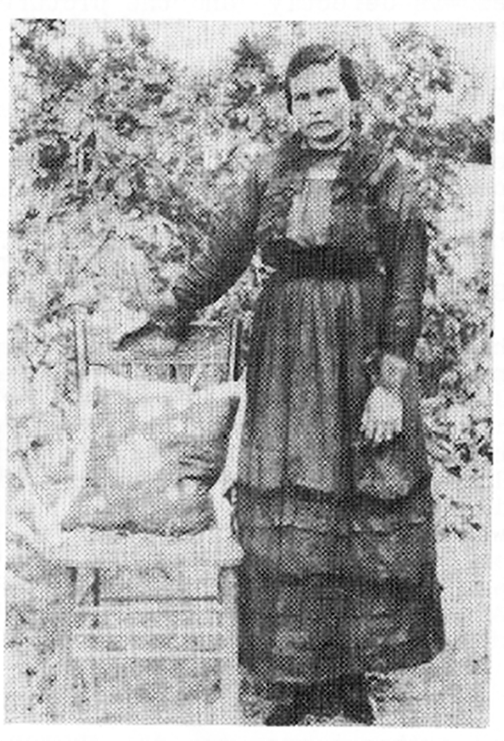

Jesús María (also known as «Chuy» & «Boots») was known throughout Alamo as «El Charro Negro». Ramón Peña of the Teatro Nuevo Mundo paid him to dress up as «El Charro Negro» & ride throughout town on a horse announcing the show when he was a teenager.

“El Charro Negro”, 1941

In October, 1947, Jesús María married Mae Kin. They left the Valley to live in Greensboro, North Carolina, where they raised one daughter Mae had by a prior marriage. Jesús became a bus driver for the city & continues in the same line of work to this day.

THE STORY OF NOT WRITING TO TELL STORIES

I didn’t write this last story. The author is María Anna Barrera.

The Story of the Afterlife of This Story

I wonder if Alonzo & Abelina in Laredo, Texas faced the immigration officer who 7 years later would ask Vladimir Mayakovsky at this same point of entry, «Moscow. That’s in Poland?» But I don’t tell this part of the story.

I don’t talk about Soviet poetry, revolution, México. I read pulp fiction about the Wild West & research cacti along the frontier. I realize that the same year André Breton excommunicated Artaud, my great-grandfather Alonzo had returned to México to seek El Niño Fidencio’s cure. This was before Artaud would write, «Man is alone, desperately scraping out the music of his own skeleton, without father, mother, family, love, God, or society»,8 [p38] fitting lines for how my great-grandfather would disappear, his last recorded words being «Salúdame a todos allá».

In the last years of his own life, Artaud would end his poem, «There’s an Old Story», with the line, «What the fuck am I here for?»15 [p227-29] They’re questions like this one that make me want to ask which stories don’t depart from anywhere in particular but remain shared. I want to know why my history moves away from itself until the time shaping it becomes foreign even to me. I end up wanting to tell someone else’s story, when I’m from a place where storytelling leads elsewhere. The people here before me knew this, or why else has the frontier’s own story changed, too?

The Rarámuri believe that at the moment of death, the deceased will exclaim, «Everybody died». Writing acts the same way. It articulates a world that passes into an afterlife, arranging & distributing all the things that are said. At the same time, I’m here in this one, translating that story.

×

NOTES

- Erban, B., 2009. Mexican Historietas: A History. [online] Sites.ualberta.ca. AVAILABLE HERE [accessed Jan 18, 2021]

- Clarin.com. 2004. Con Historietas, El Principal Alcalde De México Rechaza Cargos Por Corrupción. [online] AVAILABLE HERE [accessed Jan 18, 2021]

- Campbell, B., 2009. ¡Viva La Historieta!. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Anaya, J., 2014. Híkuri. 1st ed. Mexico City: Malpaís Ediciones.

- Enrigue, A., 2019. Ahora me rindo y eso es todo. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama.

- Artaud, A., 1976. The Peyote Dance (H. Weaver, trans.). New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

- Artaud, A., 1958. The Theatre & Its Double (M. Richards, trans.). New York: Grove Press.

- Pizarnik, A., 2019. A Tradition of Rupture (C. Heinowitz, trans.). 1st ed. New York: Ugly Duckling Presse.

- Artaud, A., 1936. “Lo Que Vine a Hacer a México.” El Nacional.

- Reyes, A. YERBAS DEL TARAHUMARA. [online] Poesi.as. AVAILABLE HERE [accessed Jan 31, 2021]

- Coulter, John M. 1894. “Preliminary revision of the North American species of Cactus, Anhalonium, and Lophophora.” in Reports on collections, revisions of groups, and miscellaneous papers, 91–132. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Rätsch, C., 2005. The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants (J. Baker trans.). Rochester, Vermont: Park Street Press.

- Merrill, W., 1988. Rarámuri Souls. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Olaya, A., 2016. “Entrecruzamientos espacio-temporales en el poema Híkuri de José Vicente Anaya.” in Caminatas nocturnas. Híkuri ante la crítica (J. Reyes González Flores, editor). Mexico: Instituto Chihuahuense de la Cultura.

- Artaud, A., 1965. Antonin Artaud anthology (Jack Hirschman editor.) City Light Books.